Living with body dysmorphia

*This article contains references to self-harm, suicidal thoughts and mental disorders.

Nobody chooses to have a mental disorder. It creeps up on you, and before you know it, it’s blown up, spinning out of control. For me, it was Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) – and this is how I learnt to live with it.

Teenage insecurity or an unhealthy obsession?

As a kid, my appearance was secondary to everything that brought me joy. Play, friends and desserts were the only things that I was concerned with. Clothes were just things I had to wear because my Mum dressed me in them. Pictures were just pictures, and how proportionate I was didn’t matter.

Looking at my baby pictures never fails to fill me with emotion because I always think that the little girl I was should never have to experience the things that she would later in her life: the wild, wide-toothed grin, her unguarded joy. If it were possible, I would want to stay in her shoes forever.

Image credit: Khalisah Zulkarnain

But, like everyone else, I had to grow up at some point, regardless of whether I was ready for it or not. If I had to point out a moment in my life where I started truly paying attention to my appearance, it would probably be when I was in my early teens. There were features that I liked about myself, but there were also those that I hated. It’s said that insecurities are taught, with the root causes being peer pressure, social media, puberty, or a combination of all 3.

Image created by: Khalisah Zulkarnain on Canva

All I knew was that my priorities changed, slowly and surely. Playing make-believe took a backseat as a new, warped form of fun took centre stage – scrutinising my body and its flaws.

Looking back, I know now that paying attention to the way I looked wasn’t necessarily problematic. It was the way my interest morphed into something sinister as my scrutiny of my body became more and more obsessive.

Signs of body dysmorphia, which I thought were normal

Obsessed with having a flat stomach

The main flaw that I found with myself was my stomach. I wanted it to be as flat as possible, and I constantly worried about how my stomach appeared to others around me. I was convinced that everyone around me knew that I didn’t have a “perfect”, flat stomach, and that they were always judging me for it..

Skipping meals & constantly checking my weight

Being paranoid about how my body was perceived meant that I developed body-checking rituals. I would skip meals, and measure my weight loss by constantly checking my collar bones: the more defined they were, the more vindicated I felt about all my unhealthy behaviours. Seeing my defined collarbones made me believe that I was getting closer to my goal of having a “perfect body” and, in turn, a flatter stomach.

Feelings of paranoia & alienation

Shame and embarrassment are normal emotions, but it isn’t normal to constantly feel that way. Being preoccupied with my flaws and paranoid meant that whenever I was around people, I would feel alienated and out of place. I could be doing nothing, but I’d still be plagued by irrational shame and anxiety.

Image created by: Khalisah Zulkarnain on Canva

Turning down social gatherings

I started to dread going out. I would turn down invitations from my friends to hang out, giving excuses that I was tired or lazy. In reality, it was my way of minimising the feelings of shame I experienced whenever I was outside.

Thoughts of self-harm

The worst of my symptoms, however, were the constant thoughts about self-harm. The obsessive hatred I had felt towards my stomach led me to have thoughts about slicing it off with scissors.

Unbeknownst to me, these were worrying signs that I was struggling with more than just insecurities about my body. I thought that they were a normal part of being a teenager.

What counts as Body Dysmorphic Disorder?

As a teenager, I didn’t know how to verbalise what I was going through. Now, I can put a name to it: Body Dysmorphic Disorder, which goes beyond being simply unhappy or feelings of mere insecurity. The signs I mistook for teenage woes are medically defined symptoms, like:

- Intense anxiety about a specific area of my body.

- Engaging in behaviours aimed at “fixing” or “hiding” this flaw.

- Extreme shame and embarrassment.

- Avoiding social situations.

- Suicide ideation or thoughts of self-harm.

Living with body dysmorphia – pre-diagnosis

Before I was diagnosed, I would appear normal on the outside. On the inside, however, was a completely different story. I developed strange, irregular habits of coping with my anxiety and avoiding feelings of shame.

A standout habit was avoiding my reflection. To be more accurate, I was obsessed with avoiding my reflection. When I say obsessed, I do mean it to the fullest extent of the word. My reflection, and by extension, mirrors, became a nightmare. In my room, it was easy to cover up my mirror with blankets or bed sheets. This had to be done in secret, though, because imagine trying to tell your Asian parents that looking in the mirror would plague you with shame. Yeah. Exactly.

In the living room stood my worst enemy – a five-panelled, mirrored cupboard that my parents loved as the highlight of our house. I couldn’t possibly cover those mirrors, so I dealt with it by running through the living room as fast as I could to get to the other side of the house.

Image for illustrative purposes only.

If you thought that was weird, I even started showering in the dark. Yes, you read that right, lights off, door closed type of dark in the bathroom, so I wouldn’t accidentally catch my reflection in the bathroom mirror.

Whenever I was outside, my environment was even tougher to control. So, I would resort to some genuinely absurd tactics to avoid looking at myself in the mirror. Public bathrooms? No-no. Changing rooms? I would avoid them at all costs.

Image for illustrative purposes only.

At one point, going out and having to obsessively be on guard against all the potential ways I could encounter my reflection became too much to handle, so I ended up not going out at all. At times when I had to go out, I was unable to enjoy myself because I was constantly battling extreme guilt, shame, and fear. The emotional toll it took on me sapped me of my energy and joy, so much so that my personality drastically changed.

I became hot-tempered and nihilistic. I started becoming a recluse and avoided the people who loved me, which caused them to be concerned about my behaviour. I would dismiss their concern and hide how I truly felt, because I believed I was being “attention-seeking” and unnecessarily burdening them with my issues.

Hiding the extent of my struggles made it tough for any of my loved ones to truly understand what I was struggling with, so the consideration that I could be suffering from a disorder never even crossed their minds.

The breaking point

If you asked me now, I would confidently tell you that my life was greatly disrupted by my internal battles. Back then, though, I think I was in denial about my ordeal and would chalk it up to “being emotional.”

For example, I would randomly cry in school because I was so overwhelmed by the stress and shame of leaving the house, being outside, and catching a glimpse of my reflection or a picture of myself.

These, my psychiatrist later explained to me, were panic attacks. Unlike regular emotional outbursts, they were instances where I genuinely got “locked out” of my own body, when I could do nothing but ride it out.

Image created by: Khalisah Zulkarnain on Canva

These attacks were usually accompanied by hyperventilating, inconsolable crying and my chest feeling so tight I could barely breathe. I would have these attacks randomly – sometimes at home, at other times in the middle of the school day.

It got to a point where these attacks happened so often that I began to think it was normal.

Going to therapy

Image credit: Psychiatry Advisor

Experts recommend seeking therapy when you’re facing overwhelming levels of distress. As a teenager, I needed an adult’s consent and funds if I wanted to go to therapy. Having to convince my parents that I needed therapy was another can of worms that I didn’t want to open. These were just some reasons why I was hesitant to ask for help.

I kept telling myself that I could deal with it and that my struggles weren’t serious enough for professional help. In hindsight, it’s a harmful mentality to have, since there shouldn’t be any shame in trying to improve your health. To put it simply, it’s similar to trying to get fit. There’s no stigma against having a fitness instructor or a professional trainer. In the same way, if you’re trying to have a healthy mind, there shouldn’t be any shame in finding help in therapy.

It was a quiet, gloomy evening, 2 years after my first panic attack, when I felt brave enough to open up to my Mum about my struggles. This was not an easy decision on my part – I was fully aware of the stigma and shame that came with mental illness and going to therapy.

A big part of why I felt willing to talk about it was because of the internet. I had the resources to read up about what I was experiencing and how I could overcome it. There were also communities online that discussed the very issues I faced, which made me feel less shame over what I thought was being “broken.” Reading constructive and open conversations about mental health empowered me to ask for help, because I wanted to finally take charge of my life.

Healthy habits I adopted & learned

From the ages of 14 to 16, I saw a psychologist biweekly to help me deal with my anxieties and emotions. I underwent a form of therapy called Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which focuses on identifying and reshaping unhelpful thought patterns.

For my recovery to last, I had to learn healthy coping mechanisms, such as:

Having a good support system

A good support system is usually made up of people you trust deeply and feel safe with. I learned that my unhealthy coping mechanism was to withdraw and isolate myself from others. This pattern of isolation meant that I was more likely to feel even more alone and hopeless, which is where a good support system comes in handy.

Image created by: Khalisah Zulkarnain on Canva

My family and friends noticed when my moods took a downturn, or when I began to isolate myself, so they would actively include me in activities or reassure me that they’re there for me. Sometimes, it was as simple as my brother coming into my room and talking about his day at school, even if I didn’t answer.

Sure, it didn’t always work, and I’d still feel overwhelmed, but I realised that being overtly reminded that I was loved and supported helped me get through those low periods quicker.

Mindfulness

Baking helped me to be present in the moment, instead of spiralling into negativity.

Baking helped me to be present in the moment, instead of spiralling into negativity.

Image credit: Khalisah Zulkarnain

Mindfulness is the practice of noticing your emotions so they don’t snowball. It was a way for me to stay grounded in the present, stopping me from feeding into dark thoughts or completely dismissing them. Whether it was breathing exercises or doing activities that kept me occupied, like watching movies or baking, this helped me the most whenever I felt like I was in the eye of the storm, trapped and powerless.

Engaging in hobbies

Some of my paintings hang on my wall as a reminder of the work I’ve put into getting better.

Image credit: Khalisah Zulkarnain

Having hobbies, I learned, was key to ensuring that I stay present and focused. The best kinds keep both our hands and mind busy – and no, doomscrolling is not a good hobby. For me, these included reading, painting, and colouring.

Think of mental wellness as a muscle. To keep a muscle strong and healthy, you’ll need to use it often. In the same vein, practising these habits consciously in your daily lives will mean that you can better manage stress and anxiety.

Adulting with an official diagnosis

Although I was equipped with the tools to maintain a healthy state of mind, my anxiety worsened before it got better. Now, the trigger isn’t just my body; I would feel anxious over anything and everything. It was like I had alarm bells ringing in my head even when nothing was happening. I was in a constant state of panic everywhere, even at home.

Later, when I turned 19, I had my first psychiatric appointment, where I was officially diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, and was prescribed medications that would help me with my anxiety. Reflecting now, I regret not getting help earlier, as I was struggling with my body dysmorphia – I think that waiting and dismissing my problems worsened my condition, causing long-term effects that I still grapple with to this day.

There’s a lot of misinformation and fear-mongering about being officially diagnosed with a mental disorder. There’s the fear that you’d be judged or prejudiced against because of your disorder. My parents, being Singaporean and kiasu, were also concerned with how it could affect my employment prospects in the future.

Whilst their concerns were valid, I like to think that these are all aspects of life that I couldn’t control. What I could control was my journey to recovery, and what I was going to do with my life. So I went through with my decision to get a diagnosis, no matter how scary it felt.

And it was worth it.

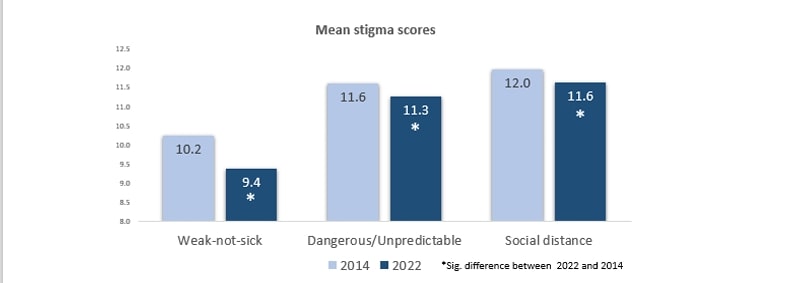

Cultural stigma on mental health

Studies show that 2% of Singapore’s adult population suffers from BDD. When you include other mental disorders like anxiety, depression, and stress, this number grows to one-third of Singaporeans aged 15 to 35.

Image credit: Institute of Mental Health

Mental health and wellness are less of a taboo topic today, but to the majority of Singaporeans, mental disorders are still something that can be “gotten over”.

Image created by: Khalisah Zulkarnain on Canva

They won’t truly go away, but it is easier to deal with when you have someone to lean on. For example, whenever I was having panic attacks, I would always call my best friend, and she would distract me by talking about her day, just to ground me.

Recovery and hopes for my future

At the time of writing, it’ll have been about 8 years since I started on this journey of repairing my mental health. The road has been long, but it has been extremely worth it. My struggles didn’t magically disappear, but I am a stronger, more resilient person with every step I take.

I don’t sprint to get to the other side of my house now, and I can walk into public toilets and changing rooms without bursting into tears. Little victories like these keep me going, and I’ve recently started feeling comfortable with taking photos of myself again.

These days, I can look at myself in the mirror and have my photo taken too.

Image credit: Khalisah Zulkarnain

Not too long ago, I was convinced that the dark days would never pass. Now I am grateful to myself for being brave and strong enough to keep going.

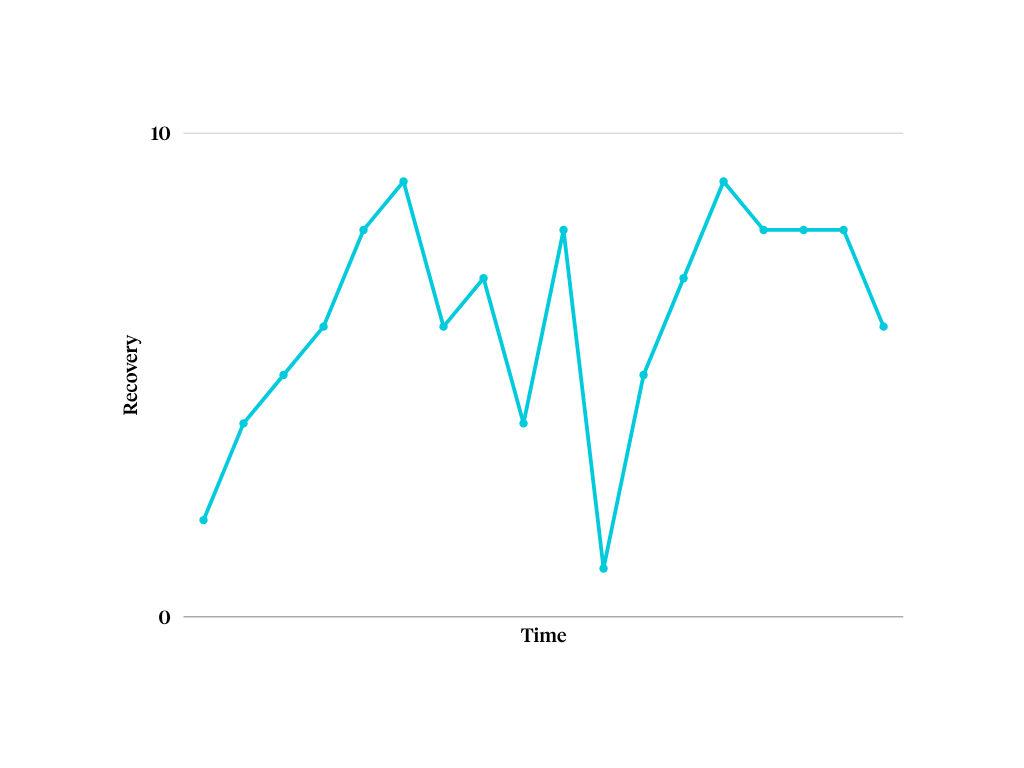

Image created by: Khalisah Zulkarnain on Canva

An important lesson that I’ve learnt is that recovery is not linear. There will always be good days and bad days. The point of mental wellness isn’t to get rid of all the bad thoughts and emotions; it’s being able to weather them and come out stronger.

It’s about being kind, patient and understanding of your own needs instead of pushing them away. It’s about pausing and taking time for yourself, even when the world seems to be leaving you behind. Most crucially, it’s about wanting to live consciously and with purpose, instead of simply going through the motions.

My journey with body dysmorphia

Everyone’s journey with anxiety, stress, and mental disorders is unique to them. You don’t need to immediately seek therapy or medical help. There are plenty of resources online, like MindSG, which provides self-care and emotional management tools for you to use to help manage your mental health. Mental health hotlines and SupportGoWhere are other important resources to keep handy for social support and outreach communities that you can reach out to in times of need.

If you know someone suffering from mental health issues, simply being there for them and understanding what they’re going through is more than good enough.

Other perspective articles to check out:

- I was an RJC failure, but I have no regrets

- How martial arts empowered an autistic boy

- Survivor’s guilt during layoff season

Cover image adapted from: The Smart Local